Pottery Background

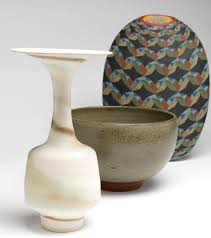

Ceramics is an age-old art form that involves the graceful manipulation of clay, a naturally occurring material rich in earthy tones, into an array of exquisite and functional creations. This enchanting process begins with the tactile experience of working with pliable clay, allowing artisans to mold it into intricate designs that reflect their vision and skill. Once shaped, the pieces undergo a transformative journey as they are carefully placed in a kiln, where intense heat brings about a remarkable change. The clay undergoes a metamorphosis, hardening and gaining durability, ultimately resulting in stunning works of art that blend beauty with utility.

This technique has been a cornerstone of human culture for millennia, evolving in tandem with the diverse needs of societies throughout history. Early pottery emerged from the hands of skilled artisans who employed primitive but imaginative hand-building techniques. Among these, the art of coiling stands out: artisans painstakingly crafted clay walls in elegant spirals, each a testament to their creativity and skill. Another method, pinching, involved the deft manipulation of clay with fingertips, allowing for the formation of intricate shapes and contours. Each piece of pottery not only served a functional purpose but also told a story of its maker’s artistry and the culture it represented.

The advent of the potter’s wheel represents a transformative leap in the art of pottery, facilitating unparalleled precision and symmetry that enables artisans to craft intricately detailed and refined shapes. Throughout the annals of history, the functions of pottery have varied widely, mirroring the rich tapestry of cultures that birthed them. These vessels have played essential roles in everyday life, serving not only as containers for storage and cooking but also as exquisite pieces for food presentation. Many hold deep ceremonial significance, while others provide a captivating canvas for creative expression. Each pottery tells a distinctive story, intricately woven with the aesthetic values, traditions, and practical necessities of the time and place from which it emerged.

The advent of the potter’s wheel represents a transformative leap in the art of pottery, facilitating unparalleled precision and symmetry that enables artisans to craft intricately detailed and refined shapes. Throughout the annals of history, the functions of pottery have varied widely, mirroring the rich tapestry of cultures that birthed them. These vessels have played essential roles in everyday life, serving not only as containers for storage and cooking but also as exquisite pieces for food presentation. Many hold deep ceremonial significance, while others provide a captivating canvas for creative expression. Each pottery tells a distinctive story, intricately woven with the aesthetic values, traditions, and practical necessities of the time and place from which it emerged.

Throughout history, pottery has experienced an incredible evolution, becoming a significant medium for artistic creativity, a marker of social hierarchy, and an embodiment of cultural identity. Although its practical use was always crucial, the pottery also developed into a lively platform for storytelling, religious rituals, and personal embellishment. In its earliest forms, the aesthetic appeal of pottery was secondary to its practical applications, featuring basic shapes and limited decorations that reflected the technological advances and natural materials available at the time.

As techniques evolved, so did the complexity of pottery. The incorporation of glazes, detailed designs, and diverse shapes transformed pottery into a form of fine art. Unique cultural styles developed, each reflecting the specific artistic values and social structures of their communities. For example, ancient Greek pottery often depicted enthralling scenes from mythology and daily life, meticulously illustrated to honor their stories. In contrast, Chinese porcelain came to symbolize luxury and imperial prestige, esteemed not just for its aesthetic appeal but also as a marker of status within the emperor’s courts. Through these different manifestations, pottery rose above its functional origins, showcasing the diverse spectrum of human imagination and cultural history.

Differences in Clay

The variety of clay is extensive and influenced by numerous factors, resulting in a broad spectrum of characteristics and applications. Here’s an overview of the main distinctions:

- Mineralogical Composition: This is the most fundamental difference. Clays are primarily composed of phyllosilicates (layered silicate minerals), but the specific minerals vary significantly. Common clay minerals include:

Kaolinite: A 1:1 clay (one layer of silica tetrahedra and one layer of alumina octahedra), known for its whiteness, refractoriness (heat resistance), and low plasticity. Used in paper, ceramics, and pharmaceuticals.

Montmorillonite (Smectite): A 2:1 clay (two layers of silica tetrahedra sandwiching an alumina octahedral layer) with high swelling capacity when exposed to water. Used in drilling muds, cat litter, and as a sealant.

Illite: Another 2:1 clay, less prone to swelling than montmorillonite. Used in ceramics and as a soil conditioner.

Chlorite: A 2:1 clay with a brucite layer between the silicate layers. Less plastic than kaolinite.

Vermiculite: A hydrous phyllosilicate that expands significantly when heated. Used in horticulture and insulation.

- Particle Size: Clay particles are extremely small, usually measuring less than 2 micrometers in diameter. Variations in particle size influence plasticity, permeability, and various other characteristics. Clays with finer grains tend to exhibit greater plasticity.

- Plasticity: This represents the clay’s capacity to be shaped and maintain its form. Clays with high plasticity are generally easier to manipulate but may be more susceptible to cracking as they dry. Factors such as mineral composition, particle size, and moisture levels affect plasticity.

- Shrinkage: As they dry, clays undergo shrinkage, with the degree of shrinkage differing based on the clay type. Significant shrinkage can result in cracking.

- Firing Behavior: Various types of clay exhibit distinct behaviors when subjected to high temperatures. Certain clays become glass-like (vitrified) at lower temperatures, while others continue to be porous. The temperature and atmosphere during firing additionally influence the final color and characteristics of the clay after it has been fired.

- Clay’s hue is influenced by impurities such as iron oxides (red, brown), manganese oxides (black, brown), and other trace elements.

- Permeability: This refers to the ease with which water and other liquids can flow through the clay. Some types of clay have high permeability, while others are nearly impermeable.

- Sources and Geographic Location: Clays from different geological locations can vary significantly in their composition and properties due to differences in the parent material, weathering processes, and depositional environments.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for selecting the ideal clay for specific applications. By skillfully blending different types of clay, one can tailor the qualities of the mixture to achieve the desired characteristics, resulting in a versatile material that meets the unique demands of various projects. Whether aiming for enhanced workability, improved firing strength, or specific aesthetic qualities, the right combination can create a customized clay that perfectly suits the intended use.

Modern Art

Contemporary art pottery includes a diverse array of techniques, styles, and movements that arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, moving away from conventional forms and embracing creativity. Important features involve a dismissal of solely decorative styles in favor of investigating form and function, the incorporation of industrial methods, and experimentation with innovative materials and glazes. Numerous important movements have had a considerable effect on contemporary art pottery.

Contemporary art pottery includes a diverse array of techniques, styles, and movements that arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, moving away from conventional forms and embracing creativity. Important features involve a dismissal of solely decorative styles in favor of investigating form and function, the incorporation of industrial methods, and experimentation with innovative materials and glazes. Numerous important movements have had a considerable effect on contemporary art pottery.

Art Nouveau (1890-1910) emerged as a fascinating artistic movement that honored the splendor of nature through flowing, organic forms. Known for its elaborate designs, pottery from this period often featured stylized floral patterns and elegantly asymmetrical shapes that reflect the fluid nature of organic elements. Prominent figures like René Lalique and Émile Gallé were instrumental in defining this captivating style, excelling in the art of merging craftsmanship with the charm of the natural world, thereby producing items that serve both practical purposes and artistic creations.

Art Deco (1920s-1930s): This movement was distinguished by geometric forms, vibrant colors, and sleek designs. Pottery from the Art Deco era often featured metallic components and opulent materials.

Mid-Century Modern (1930s-1960s): This era was characterized by a mix of styles, typically showcasing organic forms along with streamlined lines and an emphasis on practicality. Common materials included stoneware and earthenware.

Studio Pottery Movement: This movement highlighted the creative abilities and craftsmanship of individual artists, frequently employing hand-building methods and distinctive glazes. The emphasis transitioned from mass production to personal artistic expression.

Modern art pottery techniques incorporated both traditional and innovative methods:

Wheel Throwing: This technique continued to be essential, though artists experimented with innovative shapes and surface finishes.

Wheel Throwing: This technique continued to be essential, though artists experimented with innovative shapes and surface finishes.

Hand-building methods such as pinching, coiling, and slab construction provided more opportunities for personal expression and distinctive shapes.

Slip Casting: This manufacturing technique enabled the large-scale production of uniform shapes, while artists retained the ability to personalize surface features and glazes.

Artists extensively explored glazes, creating new colors, textures, and effects, such as crackle glazes and lusterware. The use of glazes evolved into a crucial aspect of artistic expression.

Ceramic Artists

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998) had an amazing artistic journey that makes her stand out in 20th-century art. She’s well-known for her fun and quirky ceramics, heavily influenced by Dadaism. Her pieces often have playful, childlike shapes and bright colors, along with some surprising textures. But don’t be fooled by the seemingly simple look—there’s a deeper connection to the artsy and philosophical movements of her time. Her ties with Dadaists and other avant-garde artists shaped her style, resulting in work that’s hard to categorize. Wood loved experimenting with different glazes and techniques, leading to a diverse collection that showcases her skill and unique vision. Her art usually has a sense of humor and pushes the boundaries of what ceramics can be.

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998) had an amazing artistic journey that makes her stand out in 20th-century art. She’s well-known for her fun and quirky ceramics, heavily influenced by Dadaism. Her pieces often have playful, childlike shapes and bright colors, along with some surprising textures. But don’t be fooled by the seemingly simple look—there’s a deeper connection to the artsy and philosophical movements of her time. Her ties with Dadaists and other avant-garde artists shaped her style, resulting in work that’s hard to categorize. Wood loved experimenting with different glazes and techniques, leading to a diverse collection that showcases her skill and unique vision. Her art usually has a sense of humor and pushes the boundaries of what ceramics can be.

Peter Voulkos (1924-1990) was a game-changer in the world of contemporary ceramics. He’s famous for his big, abstract ceramic pieces that turned the art scene on its head. Instead of focusing on pottery that was just functional or decorative, he shifted the spotlight to ceramics as pure sculpture. His works are all about bold shapes that feel raw and powerful. Voulkos often used intense techniques, breaking apart his clay creations only to rebuild them, which made for amazing pieces that reflect a deep, hands-on process. His art highlights the beauty of form and the unique qualities of clay, moving away from the idea of traditional, polished beauty.

George Ohr (1857-1918) is often called the “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” and he lived up to that name. He was a super creative artist who mostly worked on his own, making unique vessels with wild textures and funky shapes. His pieces pushed the boundaries of traditional ceramics. Ohr played around with all sorts of hand-building techniques and used eye-catching glazes and finishes, making his work stand out as visually striking and fun to touch. He was a true innovator, always experimenting with different methods and creating one-of-a-kind pieces. People often describe his style as quirky and nonconformist, reflecting his distinctive personality. The surfaces of his pots are usually uneven, showing off his experimental vibe and a clear rejection of factory-made uniformity.

George Ohr (1857-1918) is often called the “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” and he lived up to that name. He was a super creative artist who mostly worked on his own, making unique vessels with wild textures and funky shapes. His pieces pushed the boundaries of traditional ceramics. Ohr played around with all sorts of hand-building techniques and used eye-catching glazes and finishes, making his work stand out as visually striking and fun to touch. He was a true innovator, always experimenting with different methods and creating one-of-a-kind pieces. People often describe his style as quirky and nonconformist, reflecting his distinctive personality. The surfaces of his pots are usually uneven, showing off his experimental vibe and a clear rejection of factory-made uniformity.